Lt. Robert E. Lee, the Rapids, and the Steamboat

Lieutenant Robert E. Lee with his wife, Mary Curtis, and two children were sent by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to find solutions to river channel issues on the Great Mississippi which continued to cause navigation problems. Lee was transferred to St. Louis and found residence for his family in a cottage formerly occupied by Meriwether Lewis Clark and his wife Abby. Superintendent Clark’s Indian Agency Council Room in St. Louis had been converted into offices, leaving two upstairs rooms for rent. When Meriwether Lewis Clark and his wife moved to Fifth and Olive Street in St. Louis, the aging Superintendent moved in with them. This move left unoccupied the cottage which the Lee family moved in. It is probable that they had known each other at West Point being just a year difference in their graduating classes.

Lieutenant Robert E. Lee with his wife, Mary Curtis, and two children were sent by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to find solutions to river channel issues on the Great Mississippi which continued to cause navigation problems. Lee was transferred to St. Louis and found residence for his family in a cottage formerly occupied by Meriwether Lewis Clark and his wife Abby. Superintendent Clark’s Indian Agency Council Room in St. Louis had been converted into offices, leaving two upstairs rooms for rent. When Meriwether Lewis Clark and his wife moved to Fifth and Olive Street in St. Louis, the aging Superintendent moved in with them. This move left unoccupied the cottage which the Lee family moved in. It is probable that they had known each other at West Point being just a year difference in their graduating classes.

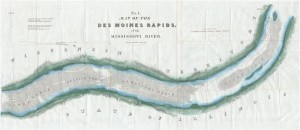

Lieutenant Lee studied previous reports and proposals to alleviate the Des Moines Rapids challenge regarding the difficulty of steamboat passage during low water periods. He found that Captain Shreve’s report in 1836 called for improvements to the Rapids by excavating a channel 90 feet wide, five feet deep, along the Iowa shore, from Keokuk to Nashville, and through the Upper Chain, near the foot of Montrose Island. Shreve reasoned:

“By pursuing this plan the navigator will have the shore for his guide, and cannot miss the channel at any stage of water. Consequently, it will not be necessary to excavate a channel more than 90 feet wide, which width can be more easily navigated than a channel 300 feet wide, following the meanderings of the natural channel that now exists between the reefs.”

But there was a secret regarding the Des Moines Rapids which but few were later made aware. From his examination and readings at Lamalee’s Chain, Lt. Lee discovered a hidden natural channel in the Des Moines Rapids which became known as the “Spanish Chute”. Lee’s plan was to follow the Spanish Chute and clear the jagged rocks causing obstructions near the river’s surface. These efforts were confined initially to the Lower and English Chains.

Under Lt. Lee’s supervision, they would drill holes by means of iron tripods standing in the water with platforms for workers to stand and for drill guides. The holes were drilled about 1 and3/4 inch in diameter through two thirds of the stratum of stone. Tin tubes were filled with about a half pound of powder then sand was added. As the drill was removed the filled tin tubes were inserted in the hole supported by the tripods and extending above the water’s surface. The ensuing explosion served to simply split the rock. The challenge was in removing the fragments. The tripods were again used in the extraction process. The tripods were repositioned and workers would pry the rocks and fasten them. They were then hoisted out of the water by crane boats. Lee’s fragmented rock removal teams were expected to keep up with the blasting teams.

Lt. Lee’s crews were only able to work for twenty days in 1838 due to high water and early fall but cleared 318 cubic yards. They were able to work for three months in 1839 and cleared 1,027 cubic yards of stone weighing about 2,000 tons.

Steamship pilots claimed that after Lt. Lee’s efforts, they were enabled to pass through the Des Moines Rapids much longer in the season because the depths had increased draw from nine to twelve inches more water than before.

Continued affirmations by Lt. Robert E. Lee, leaders within the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers, and others disheartened the land promoters in Warsaw. Efforts were being directed to deepen the natural channel water levels on the Iowa side of the river from Keokuk to Nashville, to Montrose and across to Commerce. Warsaw’s Landing site was beyond Lt. Lee’s “Spanish Chute” passage and would consequently be seldom used if excavations continued in contrast to the steamboat landing sites at Keokuk, Nashville, Montrose and Commerce. Warsaw promoters were motivated to arrange and secure a better alternative for internal improvements to serve their purposes. However, they had no means of funding their ambitious projects.

To purchase the Steamboat “Des Moines”, Peter Haws, Henry W. Miller, George Miller, Joseph Smith and Hyrum Smith signed a note payable to the U.S. Government for $4,866.38 on September 10, 1840. Charles B. Street and Marvin B. Street also purchased an interest in this steamship. They collectively signed as obligors to the note with Robert F. Smith a listed surety.

Based on referrals that they were “skillful and competent pilots with understanding of the steamboat channel”, Benjamin and William Holladay were hired as steamboat pilots. These pilots proved incompetent or were guilty of sabotage as they wrecked the steamboat by running aground upon rocks and sandbanks while outside the usual steamboat channel course. The Holladay brothers were arrested but after being released on bond they fled the state.[i]

In the aftermath, lawsuits were filed by the church leaders against the Streets as the note debt was due in mid 1841. The matter was indeed unfortunate but showed the resolve of the Saints to use the River as a commercial base for the expansion of Nauvoo.

The promissory note of Robert E. Lee to the church leaders is located at the Church History Library in Salt Lake City, Utah. The original copy of the Des Moines Rapids survey map of Lt. Robert E. Lee shown above is

[i] Dallin H. Oaks and Joseph I. Bentley, “Joseph Smith And Legal Process: In the Wake of the Steamboat Nauvoo” BYU Studies 19 (Winter 1979), 167-199